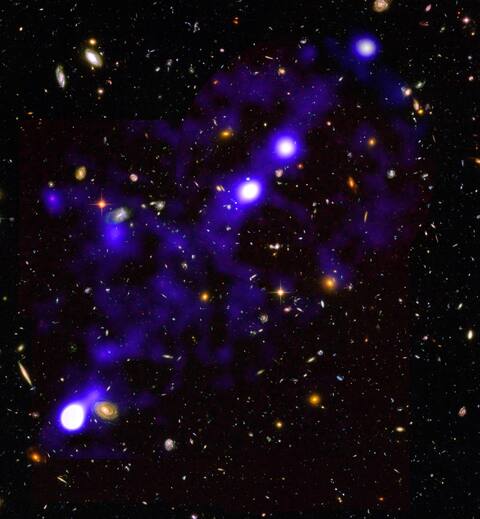

It was more than 10 billion years ago and the Universe, still young, began to activate: from this distant time we have received the unprecedented image of a web of gas filaments where the galaxies, shedding new light on their history.

• Read also: Where has the water of Mars gone?

Similar to a giant spider’s web, this “cosmic web” has long been predicted by the Big Bang model that created the Universe some 13.8 billion years ago.

It is a reservoir of gas – hydrogen – supplying the fuel needed to make stars, which when they assemble, form galaxies. It is therefore a key element to reconstruct their evolution. But it’s very difficult to detect given its distance – 10 to 12 billion light years from Earth – and low light.

The MUSE instrument, an assembly of 24 spectrographs installed on ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, achieved this, after an extraordinary observation campaign, the results of which appear in the journal Thursday. Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The international MUSE team pointed to a single region of the sky, located in the Southern Hemisphere constellation Furnace, for more than 140 hours.

After a year of data analysis, the scientists were able to capture a 3D image revealing a glow of several hydrogen filaments, spread over a large part of the sky.

The images of this web have “dethroned” those of the Hubble telescope, which until now held “the deepest image of the cosmos ever obtained”, captured in the same constellation, underlines the CNRS in a press release.

Photo AFP / Roland Bacon, David Mary, ESO / NASA

One of the hydrogen filaments discovered

Dwarf galaxies

By searching this deeply, MUSE acted like a machine to explore the past, because the further a galaxy is from Earth, the closer it is to the beginning of the Universe in the timescale. The gas filaments thus appeared as they were, “only” 1 to 2 billion years after the Big Bang, a phase considered to be initial in the development of the Universe.

“After a dark age at its very beginnings, the Universe has rekindled and began to produce a lot of stars”, explains to AFP Roland Bacon, CNRS researcher at the Center for Astrophysical Research in Lyon, who has directed the work.

“One of the big questions is to know what put an end to the dark ages”, and resulted in this abundant sequence, “called reionization”, continues the researcher.

Directly observing the glow of the filaments was thus considered a holy grail of cosmology. Because in the end, this gas, which is a residue of the Big Bang, “it is fuel, the metronome that will make galaxies build and grow to become what they are today”, according to Roland Bacon. .

“The result of this study is fundamental, we had never seen an emission of this gas on this scale, essential for understanding the process of galaxy formation”, commented Emanuele Daddi, researcher at the CEA (Commissariat à l’énergie atomique ), who did not participate in the study.

Our Milky Way, like most “nearby” galaxies, cannot provide such information, because they are too old, and much less productive in stars than was the young Universe, underlines this astrophysicist.

By combining the 3D image with simulations, the study’s authors deduced that the gas glow came from a hitherto unsuspected population of billions of dwarf galaxies (millions of times smaller than those of today ‘ hui). The hypothesis put forward is that they would have formed a phenomenal quantity of young stars whose energy would have “illuminated the rest of the Universe”, decrypts Roland Bacon.

These dwarf galaxies are too faintly bright to be detected individually with current observation means, but their probable link with the cosmic web should have important consequences for understanding the beginnings of reionization.