90 years ago, On August 9, 1930, Alexander Bovin was born, the greatest man on Soviet television. Izvestia remembers its long-term political observer on this day, as well as adviser Andropov, speechwriter Brezhnev and the first Russian ambassador to Israel.

Table Of Contents

Man without a tie

On Soviet television, they loved programs on an international topic. There were disproportionately many of them (considering that the list of DH programs was actually quite short). The most boring, perhaps, was “Studio 9” by Valentin Zorin – several men sat at the table and discussed the relaxation of international tension for an hour and a half. The most dynamic one is Today in the World, a daily (!) Foreign news release. The most fascinating (and at the same time the most propagandistic) – “The camera looks into the world” by Heinrich Borovik: they could show punks, prostitutes, and even emigrants there. well and the smartest and most solid, of course, was the International Panorama.

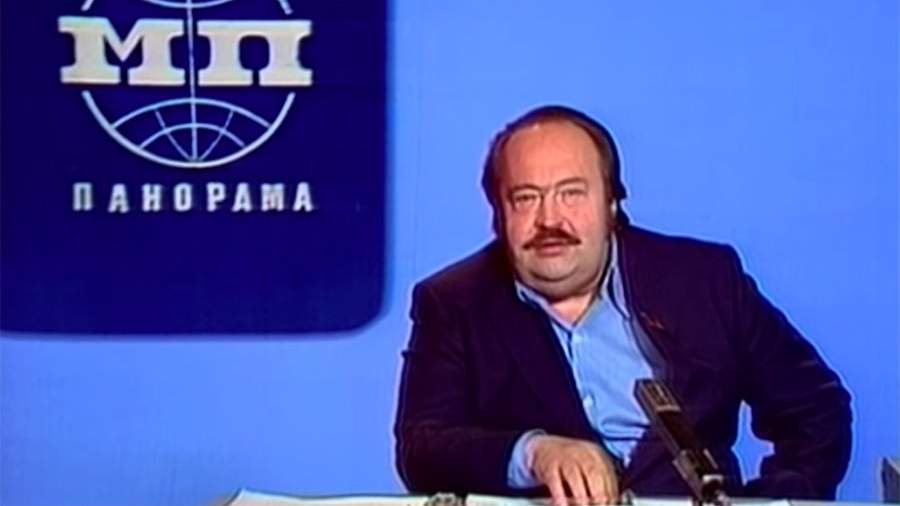

It was conducted by different people and conducted in different ways, but if an ordinary TV viewer specifically turned on the first CT program at seven o’clock in the evening on Sunday, then only if against the background of a blue backdrop, like a UN flag, an impressive figure of a man with hussars mustache – Alexander Bovin.

There was probably no less standard person in the “box”. First, the mustache (according to an unspoken rule, the Soviet TV presenter had to be clean-shaven). Secondly, a tie – that is, its absence: Bovin was the only presenter who did not wear this wardrobe item and never buttoned his jacket. Formally – because of its legendary, from youth, obesity. In fact – because he could. And thirdly, the manner of speech. Unlike his colleagues, who read official texts from the sight with the air of a prosecutor at the hearing, Bovin just told. Explained. In general, he behaved more like a university teacher, and not like an agitator and propagandist. Although, of course, he did not allow himself any political liberties (and could not even imagine such a thing), the quality of his texts – he wrote them himself – and the style of their presentation made Bovin two heads among the international journalists of the Soviet Union.

Former judge

The funny thing is that Bovin started just in court. And not by a prosecutor or a lawyer, but right away as a judge. “I was going to enter the Diplomatic Academy. I came there, and they told me: “We take only with a higher education.” Then I went to Herzen Street, where the law faculty of Moscow State University was located. I passed the interview, I had a gold medal, but I didn’t get it, they didn’t give me a dorm. I went to Rostov-on-Don, where my parents lived by that time. There, in 1953, he graduated from the law faculty of the Russian State University and was elected people’s judge of the Neftegorsk district of the Krasnodar Territory. The youngest judge was in the Soviet Union: I was barely 23 years old. “

In court, Bovin did not serve for long (and subsequently did not expand on this topic especially: nevertheless, being a judge in 1953 is not a work without specifics). He was drawn to his desk, to science. The postgraduate study of the Faculty of Philosophy at Moscow State University was an excellent place to start such activities, but the times outside the window came such that the best in any field were taken by the authorities. In the corridors of the Central Committee there were a lot of people like Bovin – smart, young, modern, in a word, “sixties” – there were many. They, of course, did not make decisions, but the role of advisers should never be overestimated.

Bovin worked as a consultant to the Department of the Central Committee for work with the Communist Parties of the socialist countries for ten years, of which the last few years was the main one. Until 1967, Yuri Andropov was Bovin’s chief. Bovin spoke of the future general secretary with respect, but without the aspiration that became fashionable in subsequent years. “Andropov was a convinced, ‘classical’ communist. A supporter of strict order. Realizing that changes are inevitable, but under the control of the party, ”Bovin later said.

In the late sixties, Bovin became Leonid Brezhnev’s speechwriter. Such a position, of course, did not exist in any staffing table – formally, he was still the head of the group of consultants of the Central Committee department. But Bovin’s influence on Soviet foreign policy at that time cannot be overestimated. Suffice it to say that he accompanied Brezhnev during the negotiations of the latter with the leader of Czechoslovakia Dubcek in 1968.

Flying hussar

In 1972, Bovin’s life took a sharp turn. Bovin himself preferred to talk about the details in a mysterious way: either he swore at Brezhnev in some company, or he wrote a harsh personal letter in which he called the Politburo members idiots. Both versions are plausible: an employee of the CPSU Central Committee, Alexander Bovin, led a lifestyle that his immediate superior Andropov tactfully called “hussarship” and for which he tactlessly preached. One way or another, one fine April day in 1972, Bovin received by special mail a package with a resolution from the Central Committee secretariat: to release him from his duties and appoint him as a political observer for the Izvestia newspaper.

This was a general’s position: 500 rubles of salary plus royalties, attachment to the Kremlin canteen (and to an even more elite group – recipients of boar meat obtained on the hunt of members of the Politburo in Zavidovo). And from the point of view of influence, as it quickly turned out, Bovin lost almost nothing. Firstly, very soon Brezhnev returned his speechwriter (albeit now on a freelance basis). And secondly, television appeared in Bovin’s life, the International Panorama. And fame and publicity are a powerful tool in the corridors of power.

A variety of rumors immediately spread about the new TV presenter. And that this is a former intelligence officer, Hero of the Soviet Union, who worked abroad for a long time. And that the author of “Malaya Zemlya” and “Virgin lands”. And that someone’s son-in-law. Reality, of course, was, as always, cooler than any fiction. Bovin did not write “Small Land”, but the 1977 Constitution of the USSR – yes. Bovin, of course, did not wear the Hero’s stars, but he did have the Order of Lenin and the State Prize. And he was also elected a member of the Central Auditing Commission of the CPSU, the second highest body of party power after the Central Committee.

At the same time, Bovin lived as before – openly and somehow completely un-Soviet. He did not suffer from pretended modesty: once, a very long time ago, he told Andropov that he would not rise above the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, but this is not bad either.… Frustrated by the propaganda work, he began, without hesitation, to ask for “ambassadors”. And – to New Zealand, because there “nothing needs to be done.”

Bovin became ambassador – a week before the collapse of the USSR. True, not in quiet Wellington, but in bustling Tel Aviv. Taking office as the ambassador of the still superpower, he worked until 1997 in the much more difficult post of a representative of a “young democracy” with a nuclear arsenal. The Israeli elite liked Bovin – thanks to the same non-standard, dissimilarity to an ordinary diplomat. He left the civil service at almost 70 – but not to retire, but to his native Izvestia. Nevertheless, with all the diversity of his own biography, he – a lawyer, an official, a political adviser, a diplomat – first and foremost always remained a journalist.