MEXICO CITY, Mexico – On a military base on the edge of Mexico City, the country’s only gun store — officially called the Directorate of Arms and Ammunitions Sales — is concealed inside a bland, concrete building. Uniformed troops serve as clerks.

Mexico is one of just three countries – along with the United States and Guatemala – with the constitutional right to bear arms. But citizens must travel from far and wide to this one place, face seemingly endless red tape and waiting periods, and pay exorbitant prices and fees.

In pre-pandemic times, the store sold an average of just 38 firearms a day – yet Mexico remains awash with illegal weapons – almost all in the hands of cartels and criminal operatives.

As violent crime surges across the nation of 126 million, activists are raising the question: Is it time to loosen firearms restrictions so ordinary people can better protect themselves and their families?

“Let’s fight to regain our peace of mind. Today Mexico needs you,” the Official Mexican Association of Firearms Users A.C. said on Facebook. “We must ensure the existence of our rights and a good future for our children.”

GANGSTER BUSTED IN MEXICAN CARTEL MASSACRE OF MORMON MOMS AND KIDS

The group has garnered more than 200,000 followers since it started its social media campaign in 2011, routinely posting updates on security and related policy issues in Mexico, but has yet to win over lawmakers despite the rise in crime.

For crime victims like Julian LeBaron, the right to self-defense has become a top issue. LeBaron, a Mexican-American, is part of an offshoot Mormon community that lost several family members last November in a cartel ambush. In a tragic case of mistaken identity, gunmen killed 14 women and children.

“We come from a long tradition from the U.S., where we believe our human rights don’t come from the government but come from the right to life, liberty and personal property. Once people claim to represent you, they claim powers to do things that you are forbidden to do,” he told Fox News. “Every person should have the means to defend themselves, especially if authorities don’t have the power to stop the crimes – especially organized crime. It becomes a vicious cycle.”

Despite Mexico’s constitutional mandate, citizens are only allowed one handgun and up to nine long arms – all priced well above U.S. market value – provided they can show proof of belonging to a hunting or shooting club.

CHINESE ‘CARTELS’ QUIETLY OPERATING IN MEXICO, AIDING US DRUG CRISIS

There are no gun shows and private sales are outlawed, with a gun owner only allowed to sell their firearm back to the government, which oversees all transactions.

Background checks can take more than six months. For most people, the high cost of guns and licenses, as well as travel to Mexico City, make gun ownership a luxury they can’t afford. A separate permit is required to carry a concealed weapon and, by most accounts, nearly impossible to obtain.

FILE PHOTO – Soldiers stand guard in front of a modified and armored truck as it is displayed to the media at a military base in Reynosa, in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas June 5, 2011. Soldiers seized a couple of modified and armored trucks at a warehouse in the municipality of Camargo during a patrol on Saturday, local media reported. According to the military, the vehicles were used by the CDG (Gulf Cartel) to transport drugs and hitmen.

(REUTERS/Stringer)

This wasn’t always the case.

In 1971, the constitution was amended to hand over all firearm control to the federal government, spurred in part to the civil unrest of the 1960s, and some experts contend that a steady erosion of gun rights ensued. That includes the passing of stringent laws banning individuals from transporting guns outside their homes without a permit from defense authorities, even if the gun was properly registered, unloaded and concealed.

“Over past decades, the country has been going through a process of systematic disarmament – classic buyback schemes and anti-gun campaigns,” said Ed Calderon, a former Mexican federal law enforcement officer and cartel expert. “And in some places, there is absolutely no security, no police presence.”

WHERE DOES MEXICO REALLY GET ITS GUNS?

Calderon argues that easing the route to gun ownership for the Mexican people would “make things better” in terms of self-defense, but stressed that the army – which controls the process – does not want to see groups of armed citizens rise up. As it stands now, all weapons must be registered and approved by the armed forces.

“They are the ones with the complete monopoly over all the guns in Mexico,” Calderon said. “Nobody wants to surrender that monopoly.”

Gun violence, meanwhile, has become a national calamity.

Almost 35,000 people – about 95 a day – were murdered in 2019, according to official records. That’s the most since 1997 and a 2.5% increase from 2018.

So far this year, the murder rate is on track to set a new record, with 2,585 slayings reported in March alone. President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has struggled to control the violence.

Even so, some Mexicans are reticent to open up gun sales.

A 50-year-old worker in Guadalajara – where the Jalisco New Generation Cartel operates – called it a “double-edged sword.”

“I don’t think loosening restrictions is a good idea. Too many of the wrong people would get them and use them,” said Juan, who gave only his first name for fear of retribution.

At the same time, he bemoaned that ordinary citizens are essentially defenseless while criminals and corrupt authorities are armed to the teeth.

“It isn’t fair. It is all intended to keep the population under control. Anyone I have known to have had a gun either denied it or ended up throwing it away or got into serious trouble,” Juan said. “As for self-defense, the wealthy hire high-level guards, ex-soldiers and the like.”

President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador stands in front of an image of a raffle ticket featuring the presidential plane, in his morning press conference at the National Palace in Mexico City, on Feb. 7, 2020. Lopez Obrador announced that the raffle of the Boeing Dreamliner will be symbolic, awarding total prize money of $100 million, which lottery tickets state is “equivalent to the value of the presidential jet.”

(AP/Mexico’s Presidential Press Office)

Juan said the cartels offer security, but it comes with a price.

“More rural areas prefer to side with them,” he said. “But if you get in their way, they will take you out, and there is nothing anyone can do to help you.”

Several citizens interviewed by Fox News said that they would support greater civilian gun ownership provided there was robust firearms training. But some said that education is sorely lacking today in cartel-dominated rural areas.

Mexico-based journalist Ioan Grillo, author of the forthcoming book “Blood, Gun, Money,” noted that while he can empathize with the desire many have for personal protection, gun ownership could make a dire situation worse.

“A lot of the problems in Mexico aren’t related to common crime; it is about major organized crime. If I was carrying a pistol and was stopped by 10 guys with AK-47s, it isn’t only useless, it is going to be provocative in that situation,” Grillo said.

Since 2006, when a crackdown against the illicit drug trade was reignited, the government estimates that more than 250,000 people have been slaughtered. But tens of thousands are still missing, many more have never even been reported as having disappeared, and only a small number of perpetrators have been prosecuted.

Gun rights activists were further enraged last October when security forces stumbled upon the son of convicted drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman in the northern city of Culiacan, but were ordered to release him by the president to avoid an escalation in tensions.

Mexican National Guardsmen block the border crossing between Guatemala and Mexico in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Saturday, Jan. 18, 2020. More than a thousand Central American migrants surged onto the bridge spanning the Suchiate River, that marks the border between both countries, as Mexican security forces attempted to impede their journey north. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

To many, it was clear evidence that not even the country’s leaders can control the carnage.

LeBaron and other members of his family have spoken out in favor of loosening gun restrictions, but he doesn’t expect to see changes anytime soon.

“The first step is more accountability. The government needs to be able to fire anyone – officials, law enforcement – engaging in the corruption and the cycle of violence,” he said. “The connection between organized crime and the government is so obvious that it is sickening. I don’t believe in violence, but I believe in being able to protect my family.”

Some critics question the potential impact of looser Mexican gun laws on national security in the U.S.

David Kopel, a gun rights advocate and adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, dismissed such concerns.

“I don’t think there would be significant dangers to the U.S. if Mexicans were allowed to defend themselves legally,” he said. “There are already plenty of guns in the U.S., so the possibility of northbound arms smuggling seems remote.”

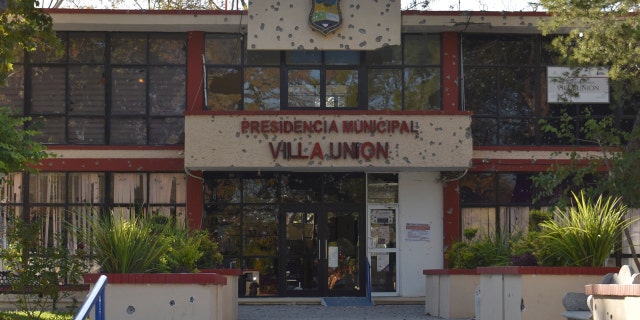

The City Hall of Villa Union is riddled with bullet holes after a gun battle between Mexican security forces and suspected cartel gunmen, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2019.

(AP Photo/Gerardo Sanchez)

Kopel expects the incoming Biden administration will make cartel violence south of the border a key foreign policy concern.

“Trump’s approach has probably made things better by improving border security. And, of course, the Trump administration – unlike the Obama and Bush administrations – didn’t allow ATF to mastermind gun-smuggling operations into Mexico, for the purpose of later ‘finding’ the crime guns and using the finding to bolster the argument for gun control in the U.S.,” Kopel said, referring to the controversial 2006-2011 “Fast and Furious” operation.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

But he said there’s little chance that the U.S. will support expanded Mexican gun rights.

“Biden will likely return to the Obama policy of using Mexico’s problems as a pretext to push for restrictions on gun owners in the United States,” Kopel said.