Masonic specialist in creativity Sumarokova, who has been working for almost two decades in the more “stern” sphere of glossy magazines, Marina Stepnova declared herself as a prose writer back in 2000. Her second novel, The Woman of Lazarus, received the Big Book and was unexpectedly favored by the overseas The Guardian. This is the fourth experience in the big genre that has attracted the attention of the critic Lydia Maslova, who is presenting the book of the week – especially for Izvestia.

Table Of Contents

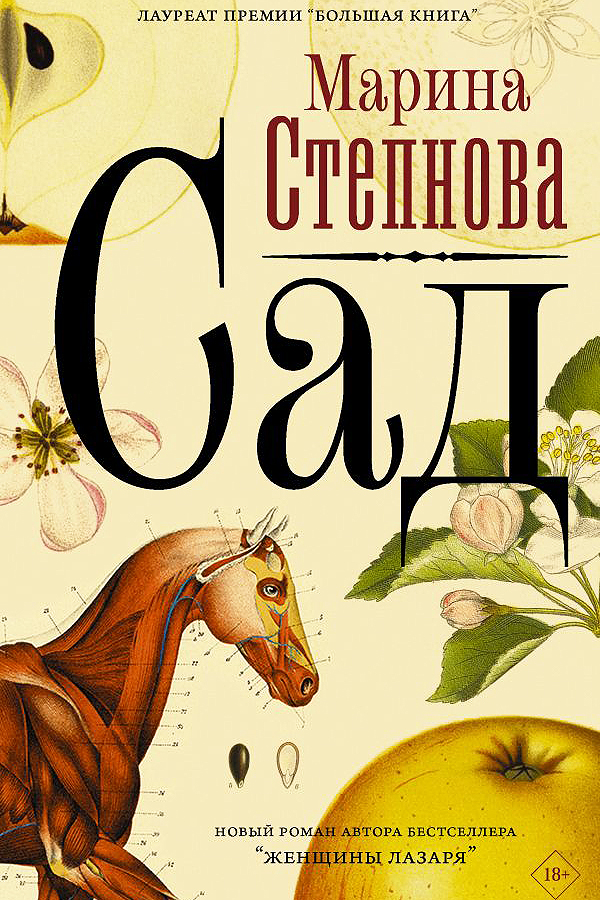

Marina Stepnova

Garden

Moscow: AST Publishing House: Edited by Elena Shubina, 2020 .– 412 p.

The first chapter of Marina Stepnova’s new book begins with the exclamation “What a lovely Natasha!” Recognizing a quote from the inner monologue of Natasha Rostova, who admires herself, will not be difficult for a reader who has already coped with the first test of the quest novel – an epigraph that must be read backwards. This does not make it much clearer (one of several lines reads: “about a wolf’s tooth, about choking and coughing”), and the meaning of this charade will be explained many pages later. The ability to quickly read in reverse and in mirror reflection is just one of the many original features inherent in the heroine of “Garden”, named after the heroine of Tolstoy and responding to the home name “Tusya”.

The daughter of a 44-year-old princess (this age of a woman in childbirth is not a very familiar phenomenon even now in Russia, and in the second half of the 19th century, when the action takes place, she is completely indecent reprimand, even in a legal marriage), even before birth, is in many respects an exceptional case, and as it grows up pleases the reader with a varied assortment of oddities and extravagant antics. However, in the work of Stepnova, in principle, it is difficult to meet the so-called “ordinary” people, who in fact almost never exist in life, no matter how colorless it may seem. They exist only in bad literature and “correct” films, and, perhaps, in the painting of the Itinerants.

Stepnova’s garden, who loves paradoxical and intricate human combinations and constellations, brings to mind rather another pictorial reference – “The Garden of Earthly Delights” by Bosch. In one of the episodes, by the way, a curious special effect is mentioned – a candle that “danced, moved, turning Rembrandt into Bosch.” AND as for the cinematic associations, “Garden” at times resembles a thriller like “The Exorcist”, when a very monstrous chton suddenly creeps out of the wonderful girl Tusi.

Starting to speak only a few years after birth, which she spends mainly in the stable, being crazy about horses, Tusya first of all masters the brutal vocabulary of grooms. So already her first word, an obscene anatomical term, is not possible to quote in the review, and then the girl begins to vomit, like uncontrollable fetid vomit, streams of swearing.

The role of “exorcist” here is played by the person closest to Tusya – an elderly family doctor who replaced her father after he cowardly ran away from the stubbornly silent girl, considering her defective. The fact that blood kinship sometimes means nothing, in contrast to spiritual ties, sometimes predetermined from above, fatally metaphysical, is one of Marina Stepnova’s favorite themes. In The Garden, this dichotomy of animal and human kinship is explored with maximum psychological depth.

Stepnova quite ingeniously uses classical Russian literature as fertilizer for her magnificently blossoming “Garden”. In addition to the disposal of Natasha Rostova, Karamzin, Nabokov, Mandelstam are used, not to mention Chekhov, to whom both the title of the novel itself and the fate of the notorious garden refer. He, however, appears here almost as an animate being, most actively participating in the plot along with humanhuman characters, and not only serves as a symbol of something sublime, as in Chekhov’s play. In general, the Stepnovsky garden on a noble estate not far from the real-life village of Khrenovoe (emphasis on “o”) in the Voronezh province is much more complicated and terrible than Chekhov’s. This is such a garden, from which the first letter easily falls away, you just have to look behind it:

“Now, in this juicy, over the edge, bulging, almost obscene garden, she suddenly realized that for twenty-five years she had lived with her husband just side by side, as if they really were not people, but well-groomed domestic dogs, so long accustomed to a common bowl and stove bench, that between them all vital, animal differences have been erased “

Each in its own way unfortunate inhabitant of Stepno’s multi-figured structures is as if dotted with keyholes, into which you can peep its spiritual contents, which often cause the same thrill as if you were drilling living flesh with a drill in front of your eyes. Stepnova again successfully appears in a specific subgenre of horror, which can be described as “the horrors of family life.” Although familyless life here is scary in its own way, a person who is closed on himself is still not exposed to such risks as any interaction between people is fraught with, even if it arises from the best intentions and begins in the happiest way.

Photo: publishing house “AST”

Like other most powerful novels by Stepnova (The Surgeon and The Women of Lazarus), The Garden at times requires a strong nervous system, and above all, the ability to look at some rather disgusting physiological things without turning away, which is inherent in doctors. Stepnova, the doctor’s daughter herself, continues to build up terrifying virtuosity in describing morbid conditions bordering on lethal outcome (in The Garden, for example, exhausting childbirth stretching over several days), as well as the most severe bodily injuries. In the episode, which depicts in detail the state of a doctor mutilated during a cholera riot in St. Petersburg, you just want to close your eyes, like on some terrible self-mutilating slasher. But it is also impossible to close your eyes, or, say, put aside the book, because sometimes frightening Stepnov’s texts tend to suck you in. HThe more disliked characters appear on the pages, the more difficult it is to look away from them (a similar effect is produced, so as not to go far for an example, “The village of Stepanchikovo and its inhabitants”).

In “Garden” one of the most unpleasant turns out to be Tusin’s completely worthless future husband, whose background is interwoven with an interesting relationship with the extremely charming Alexander Ulyanov, who has a brother, Volodya, “bursting, obnoxious, always pestering everyone with chess.” The novel ends with a letter from poor Alexander to a friend, unread and cowardly torn, of which only a couple of syllables remain.

Stepnova, with her author’s will, restores the lines that have flown away into oblivion, or rather, a single phrase, which is repeated, according to the writer’s somewhat exalted expression, “a thousand times in a row”. But here, taking pity on the reader, the author does not even resort to Nabokov’s trick: “repeat, typesetter, until the page runs out”, but is content with only five times repetition – nevertheless, for all Marina Stepnova’s ruthlessness to the reader, mercy sometimes knocks on her stern heart.