When fans tune in as the NBA season resumes at Disney World on Thursday, they will be watching a game with a different feel.

On gleaming courts refashioned from ballrooms, in a basketball ‘bubble’ protected from coronavirus at the Florida resort, three words will be stencilled alongside the enormous NBA logo: ‘Black Lives Matter’.

Jerseys ordinarily emblazoned with well-known surnames – prized products sold to fans around the world – will instead carry activist slogans: ‘Justice Now’, ‘See Us’, ‘Hear Us’, ‘Respect Us’, ‘Love Us’.

The stands will be empty and silent, but one message is already echoing loudly: the NBA wants to talk about racism.

Even before the shocking death of George Floyd triggered a national reckoning, sport had long been a vehicle for protesting against what has been called America’s Original Sin.

Big moments – like the raising of a fist by Tommie Smith and John Carlos in a black power salute as the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ played at the 1968 Olympics – have become iconic images.

More recent gestures, like those sparked by Colin Kaepernick’s refusal to stand for the national anthem, have become a contentious point of political debate in the United States.

Race, as the respected San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich puts it, is the “elephant in the room in our country” – one that has come charging into the locker room on many occasions.

Of all sports, basketball is arguably the most obvious place for an unvarnished conversation.

From its earliest days of being popularised as entertainment by the Harlem Globetrotters, to a sport still primarily played by black athletes and, in the US, watched largely by ethnic minority fans (two-thirds of those who tuned in during 2016-17 on US TV were non-white), race has figured prominently in the NBA.

The league says it will embrace the conversation head-on this time. But will it be any different than in the past – and will it make a difference?

Black players have always been aware of the thin line that separates them from a life of professional success and a far different fate.

As the youngest of three sons of a single mother growing up in inner city Philadelphia, Rasheed Wallace realised early that it would be hard going, as did everyone around him.

“The stakes are high, the stakes are real high,” Wallace – who played for 2004 champions the Detroit Pistons – tells the BBC. Growing up poor and with few opportunities, sports are one of the few ways young black men, especially, can conceive of success.

“You see a lot of black parents getting on their kids, no matter [whether] it’s football, basketball, baseball or any sport. It’s like, ‘look – this could be our ticket out of here’,” he says.

“There’s a standard you have to live up to. And for us, being black kids in the ghetto, we know that. That if I can make it, I got a chance to make it better for my family.”

But that success does not change how the world views a black man when he is out of team uniform, Wallace believes.

Stephen Jackson was sitting on his living room sofa in late May when his phone began to light up with messages.

“I opened one from a close friend and it said: ‘Do you see what they did to your twin in Minnesota?’,” Jackson, a former San Antonio Spurs shooting guard, tells the BBC. He knew immediately what it meant.

George Floyd had been a close friend for more than 20 years.

Floyd, an imposing Texan of over 6ft 8in who was 46 when he was killed, and Jackson, 42, looked so much alike they called themselves twins.

Today, one has an NBA championship ring and network sports podcast, and the other is dead.

“That could have been me,” Jackson says. “I see myself down there because we look so much alike. I definitely see myself getting murdered in the same fashion by a cop.”

Wallace agrees. “For sure, it could have been me. Especially with my attitude, the way I am.”

He adds: “Now I think [race] is even more of a bigger burden. It’s almost like it’s a danger to stand up, to be black. It’s a danger for you to be jogging in a neighbourhood. It’s almost to the point where black men, we’re the targets.”

Floyd had been a star athlete in his younger days, and was recruited to play basketball for a university team. Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin has been charged with second-degree murder and manslaughter in relation to his death. Three other officers were also charged with aiding and abetting murder. A tentative trial date has been set for March 2021.

For those like Jackson and Wallace, talent has kept misfortune at bay, but it is no guarantee of a happy outcome.

Asked who he would call basketball’s greatest of all time, the legendary Kareem Abdul Jabbar did not name Michael Jordan, Wilt Chamberlain or some other household star but Earl Manigault, a street ball player he knew in Harlem, New York as a youth.

Manigault is little known, for he never made it into the professional ranks. Seen as a prodigy on street courts, he instead went from an impoverished youth to difficult adulthood, becoming addicted to heroin and serving time for drug possession.

“For every Michael Jordan, there’s an Earl Manigault,” Manigault once told the New York Times. “We all can’t make it. Somebody has to fail. I was the one.”

This is the realisation the rest of the country has been waking up to in 2020 – that the cards are stacked this way in black America. The NBA says it wants to bring it into further focus.

According to the league’s 2020 handbook, a “central goal” of the season will be to use the NBA’s platform “to bring attention and sustained action to issues of social injustice, including combating systemic racism, expanding educational and economic opportunities across the black community, enacting meaningful police and criminal justice reform and promoting greater civic engagement”.

Some, including Jackson, are sceptical. This is not the first time the league has made public statements on racial justice.

In 2014, the league allowed players to wear T-shirts bearing the words ‘I can’t breathe’ before matches. Eric Garner, a black man from New York, had uttered the words before he died in a police chokehold during an arrest.

The same year, commissioner Adam Silver ejected Donald Sterling, then owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, from the league after racist remarks he made about black players emerged.

The league publicly condemned Sterling and the team was sold.

But critics say that on the metrics that matter, nothing much has changed. Three-quarters of players in the NBA are black, but only one of the 30 teams has a black majority owner – Michael Jordan of the Charlotte Hornets. As recently as 2017, there were only three black general managers. Now there are six.

After retiring from playing, Wallace served as an assistant coach for the Pistons for a season. There were not many like him in the league.

“We don’t get the quote-unquote ‘white opportunities’ – to be that GM, to be that head coach, assistant GM or partial owner, whatever. That’s always up to the white people,” he says.

It is another closed door yet to be fully opened – but needs to be, he says, so that youngsters in neighbourhoods like the one he grew up in can see they “don’t have to just play basketball or football or baseball to become someone, to become a significant person in my community, or to even make a lot of money”.

He adds: “That’s the only outlet that we see as young black men: I gotta make it in basketball or football or baseball. And that’s all that we’re offered.”

It would be hard to argue there has not been any progress.

The arc of basketball history has bent toward a bit more justice since the 1920s – when black athletes were forced to stay in segregated hotels while travelling through the American South – or even the 1980s, when white players were paid $26,000 more on average, despite poorer performances on the court.

Black players today have far greater power and command greater respect as public figures, plus the earnings to match. Playing for the Harlem Globetrotters in the 1930s was worth as little as $7.50 a game – $144 (£111) today – according to basketball historian Doug Merlino, but it was often a choice between that or a life of menial labour.

The current top five NBA players, all of whom are black, will make a collective $192m (£147m) on salaries alone over 2019-20.

There are those – fans, commentators and players themselves – who will see the limits of sports activism, or reject it altogether.

“Shut up and dribble” was the response from Laura Ingraham, a right-wing news anchor, when in 2018 LeBron James gave an ESPN interview criticising President Trump’s attitudes on race.

That Ingraham did not have similar advice more recently for Drew Brees, a white American football player, to keep out of politics have, in many people’s view, lent her previous comments a racial tinge. (Brees had made remarks rejecting the take the knee protest in his sport.)

But the sentiment is not unique to conservative news figures. On plenty of forums and comments below sports talk shows, are complaints from fans decrying the forays of their favourite court stars into politics.

Others see a heavy dose of hypocrisy in how players, former players and the league handle divisive political issues.

Jackson, for example, was engulfed in controversy after making anti-Semitic comments on social media.

He said his comments were taken out of context, but the episode extinguished a measure of sympathy for his racial activism among many. For some others, it nullified all goodwill entirely.

In a column for the Hollywood Reporter, Jabbar said Jackson’s comments “undid whatever progress his previous advocacy may have achieved” by himself committing “the kind of dehumanising characterisation of a people that causes the police abuses that killed his friend, George Floyd”.

He wrote of “a very troubling omen for the future of the Black Lives Matter movement,” adding: “So too is the shocking lack of massive indignation.”

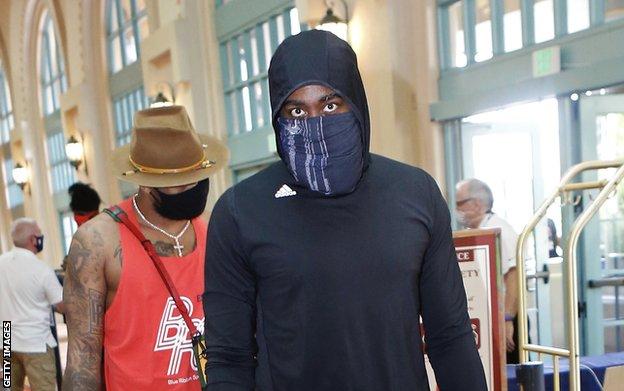

More recently, Houston Rockets star James Harden drew fury when he was photographed wearing a mask with an emblem supporting ‘Blue Lives Matter’, a counter-organisation to Black Lives Matter that backs police.

Harden said he was not trying to make a statement – he just thought that the design ‘looked cool’ and covered his beard.

Detractors will say it proves sportsmen may not be the best agents of political messaging, and that it distracts from the experience fans are paying for with their time and money – a reprieve from politics.

And if politics should be allowed to enter in, where should the line be drawn? Another row was stirred up after Josh Hawley, the Republican Missouri Senator, wrote to Silver to complain the NBA is allowing Black Lives Matter-themed slogans, but not those supporting US troops, or backing free speech in Hong Kong.

The senator accused the NBA of “excusing and apologising for the brutal repression of the Chinese Communist regime”.

“Free expression appears to stop at the edge of your corporate sponsors’ sensibilities,” he chided.

But even if thorny questions remain, there is no doubt that the zeitgeist in America has shifted more broadly.

Poll after poll in 2020 shows that, unlike in the past, Americans are largely accepting the idea that racism exists and plays a part in the many social ills black people face in the country.

The “myth” that America’s problems with race are largely overcome is being challenged, whether in basketball or in the greater society, believes Popovich, the 71-year-old Spurs coach.

“You can’t go on and enjoy your life if you don’t understand what has happened to so many,” he says.

As for the league’s race campaign, he is realistic about the prospect of influence.

“Fans are like any other group of people – some will get it, some will understand, some will just enjoy the games and move on,” he says.

“Others will hopefully get involved in being part of the solution of being anti-racist, but that’s a pretty individual thing.”

After all, sport – as much a cultural product of the times as any entertainment – can only reflect the realities of its era. In 2020, the reality is that to be black is in itself to be political, and that position is not a choice, whether you are a basketball star or a bouncer.

The slogan stencilled beside the NBA logo is a reminder. The lives of so many of the men dribbling, jumping, performing feats of athleticism are black ones – and they matter not just on the court.