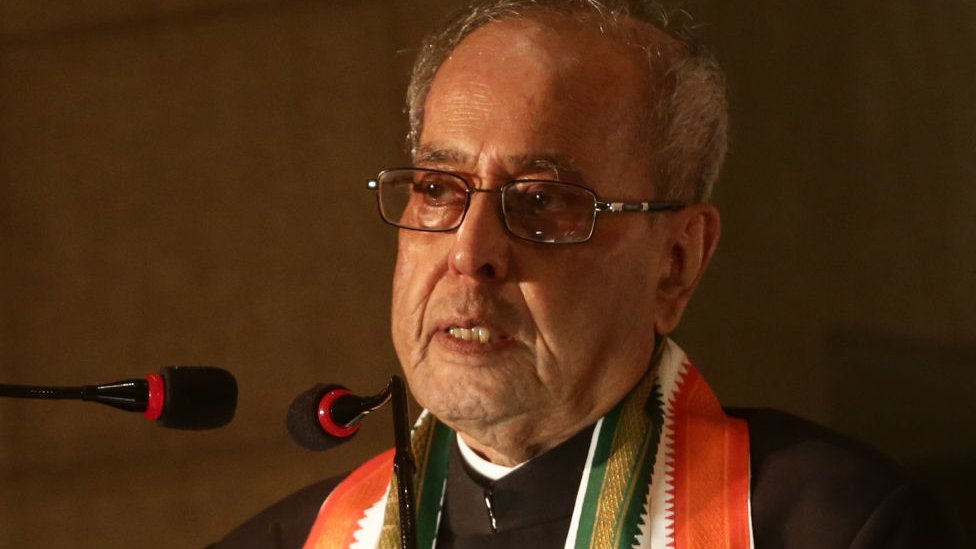

image copyrightGetty Images

India’s former president Pranab Mukherjee has died 21 days after it was confirmed that he had tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

The 84-year-old was in hospital to remove a clot in his brain when it was discovered he also had Covid-19.

Before serving as president between 2012 and 2017, Mr Mukherjee held several important portfolios during his 51-year political career.

These included the finance, foreign and defence ministries.

His son, Abhijit, confirmed the news in a tweet.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi praised Mr Mukherjee’s contribution to the country, saying the former president had “left an indelible mark on the development trajectory of our nation”.

“A scholar par excellence, a towering statesman, he was admired across the political spectrum and by all sections of society,” Mr Modi wrote on Twitter.

The job of president is largely ceremonial but becomes crucial when elections throw up fragmented mandates. The president decides which party or coalition can be invited to form a government.

Mr Mukherjee didn’t have to take such a decision because the mandate was clear during his presidency. But he showed his assertiveness in other decisions, such as rejecting the mercy petitions of several people who had been sentenced to death.

Mr Mukherjee also served on the boards of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Most of his career was with the Congress party which dominated Indian politics for decades before suffering two consecutive losses in 2014 and 2019 to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Mr Mukherjee joined the party in the 1960s during the tenure of then prime minister Indira Gandhi whom he had described as his mentor.

In 1986 he fell out with the Congress leadership and started his own political party, but returned two years later.

image copyrightGetty Images

A parliamentarian for 37 years, Mr Mukherjee was widely known as a consensus-builder. Given that consecutive governments before 2014 were built on coalitions, this was an important and valued attribute.

However, Mr Mukherjee’s larger ambition – of becoming India’s prime minister – was never realised.

He was overlooked for the post twice – after the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and after his party’s unexpected election win in 2004.

Manmohan Singh, a trained economist who was chosen as the prime minister, later said that Mr Mukherjee had every reason to feel aggrieved. “He was better qualified than I was to become the prime minister, but he also knew that I have no choice in the matter,” Dr Singh said.

Pranab Mukherjee was one of India’s most astute politicians.

As one of the leading figures of the Congress party, he held every key ministry in India – commerce, defence, external affairs and finance – over a chequered half- a-century-long political career.

What the diminutive leader lacked as a politician with a mass base – he was mostly elected to the upper house of the parliament – he made up with his keen sense of realpolitik and formidable managerial skills.

During the two-term Congress-led government which ended in 2014, Mr Mukherjee deftly negotiated the choppy waters of an unwieldy and often fractious coalition.

He worked tirelessly at building consensus on a raft of rights-based legislations relating to matters like food security and right to information that helped his party gain political heft and popularity.

His record as a finance minister in the second term was less stellar: the economy overheated, inflation peaked and interest rates went through the roof. Critics called him one of the “worst” finance ministers India ever had.

As the 13th president of the republic, Mr Mukherjee walked a fine line, having good relations with his party’s arch foe and now Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his own Congress party leaders.

In many ways, he was a remarkable exception in the rough and tumble of Indian politics: a calm bipartisan leader and a dour consensus builder with an encyclopaedic memory.

When Mr Mukherjee was appointed India’s president in 2012, he was widely acknowledged as being the most experienced politician by far to take up the post.

His tenure as president saw him reject up to 18 bills that were sent to him for assent. Presidents generally do not reject bills sent to them.

He also rejected 30 mercy petitions from death row convicts – the highest by far of any Indian president.

As a result, Afzal Guru – convicted of involvement in the 2001 attack on India’s parliament was hanged in February 2013.

Yakub Memon, who was convicted of financing the 1993 terror attacks in Mumbai, and Ajmal Kasab, one of the gunmen in the 2008 Mumbai attacks, were also hanged during his tenure.