image copyrightGetty Images

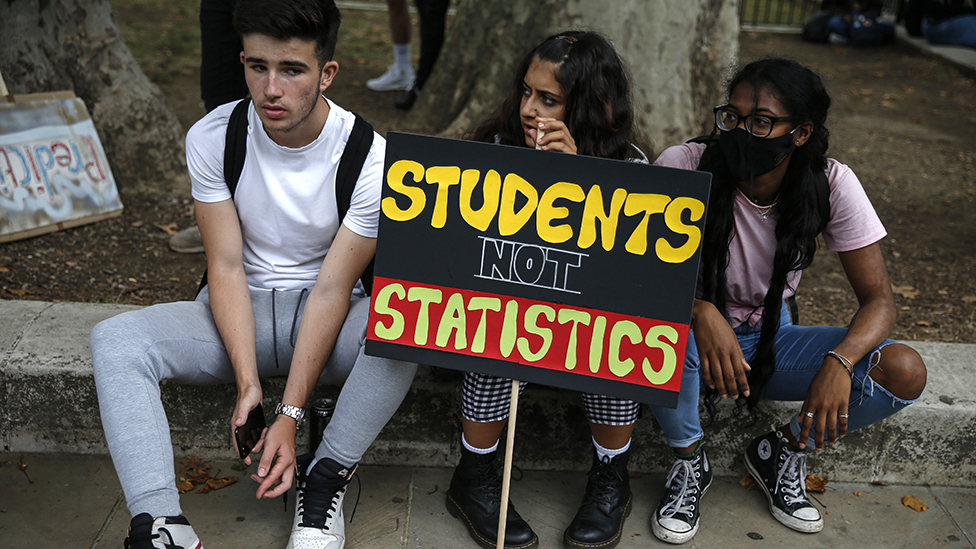

A-level students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland will have their grades based on teacher assessments rather than an algorithm, after uproar on last week’s results day.

About 40% of A-level results were downgraded by exams regulator Ofqual, which had used a formula based on schools’ prior grades.

a similar change in Scotland, where pupils also had their exam results upgraded.

Table Of Contents

How were A-level grades originally decided?

Students in the UK did not sit exams this year because schools were closed following the coronavirus lockdown.

In England, A-level students were given grades by the official exam regulator, Ofqual.

Teachers were asked to supply for each pupil:

- The grade they were estimated to receive in an actual exam

- A ranking compared with every other pupil in their class

These were combined in a mathematical model – or algorithm – with the school’s previous performances in each subject.

The idea was that in each school, students would be given similar grades to those awarded to their school in the previous few years.

The teachers’ rankings would decide which of those pupils received the top grades in their particular school.

Ofqual said this was a more accurate way of awarding grades than simply taking teachers’ assessments for their students.

It argued that teachers were likely to be more generous in assigning an estimated mark, and this might lead to grade inflation.

Similar algorithms were applied for A-level pupils in Wales and Northern Ireland. They were also used in Scotland for the Scottish Higher qualification, which is broadly comparable with A-levels.

What happened?

When A-level grades were announced in England, Wales and Northern Ireland on 13 August, nearly 40% were lower than teachers’ assessments.

There were similar issues in Scotland.

In England, 36% of entries had a lower grade than teachers recommended and 3% were down two grades.

What’s more, the downgrading affected state schools much more than the private sector.

The prime minister defended the system as “robust”, but there was widespread criticism from schools and colleges, as well as from the opposition and some Conservative MPs.

Why did some schools feel they had been treated unfairly?

However, by basing it so much around previous school performance, a bright student from an underperforming school was likely to have their results downgraded through no fault of their own.

Likewise, a school which was in the process of rapid improvement would not have seen this progress reflected in results.

In Scotland, figures showed that the Scottish Higher pass rate for pupils from the most deprived backgrounds was reduced by 15.2 percentage points, compared with only 6.9 percentage points for the wealthiest pupils.

Why did it benefit private schools?

Private schools are usually selective – and better-funded – and in most years will perform well in terms of exam results. An algorithm based on past performance will put students from these schools at an advantage compared with their state-educated equivalents.

Where there were fewer than five pupils studying a subject at a school, their grades were decided only on the basis of teachers’ estimates, which were “typically higher” than Ofqual’s assessments.

Where there were between five and 15 entrants for a subject, teachers’ assessments would also be given more weight.

Were there other protections in place?

A-level students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland all had their original grades informed by algorithms.

However, some other protections were in place or later added:

- In Wales the final mark could not be lower than a pupil’s grade at AS-level, which are taken the year before A-levels. They count towards 40% of the final grade.

- In England, students unhappy with their grades were told they could appeal using mock results or sit exams in the autumn

In Scotland, after criticism over the Higher results, the government reverted to teacher assessed grades.

What happens next?

It isn’t entirely clear yet.

Some students will now have higher grades, so might consider looking at different universities or colleges. The process for doing so hasn’t been outlined in full and pupils should keep in contact with their schools and Ucas, the university admissions system.

Alistair Jarvis, the head of the university body Universities UK, has said they “will do everything they can” to help students over the next few days. However, he has also highlighted the “challenges” facing universities, such as capacity, staffing and facilities.

It also means that this year will see a considerable amount of grade inflation, the main reason the algorithm was introduced in the first place.

Grade inflation is when grades increase substantially, making it difficult to compare one year with another. This can cause problems, because students from this year might compete with students from previous years for jobs, apprenticeships or university places.